Margaret Mathews-Berenson (Peeky) on the legacy of Deborah Remington

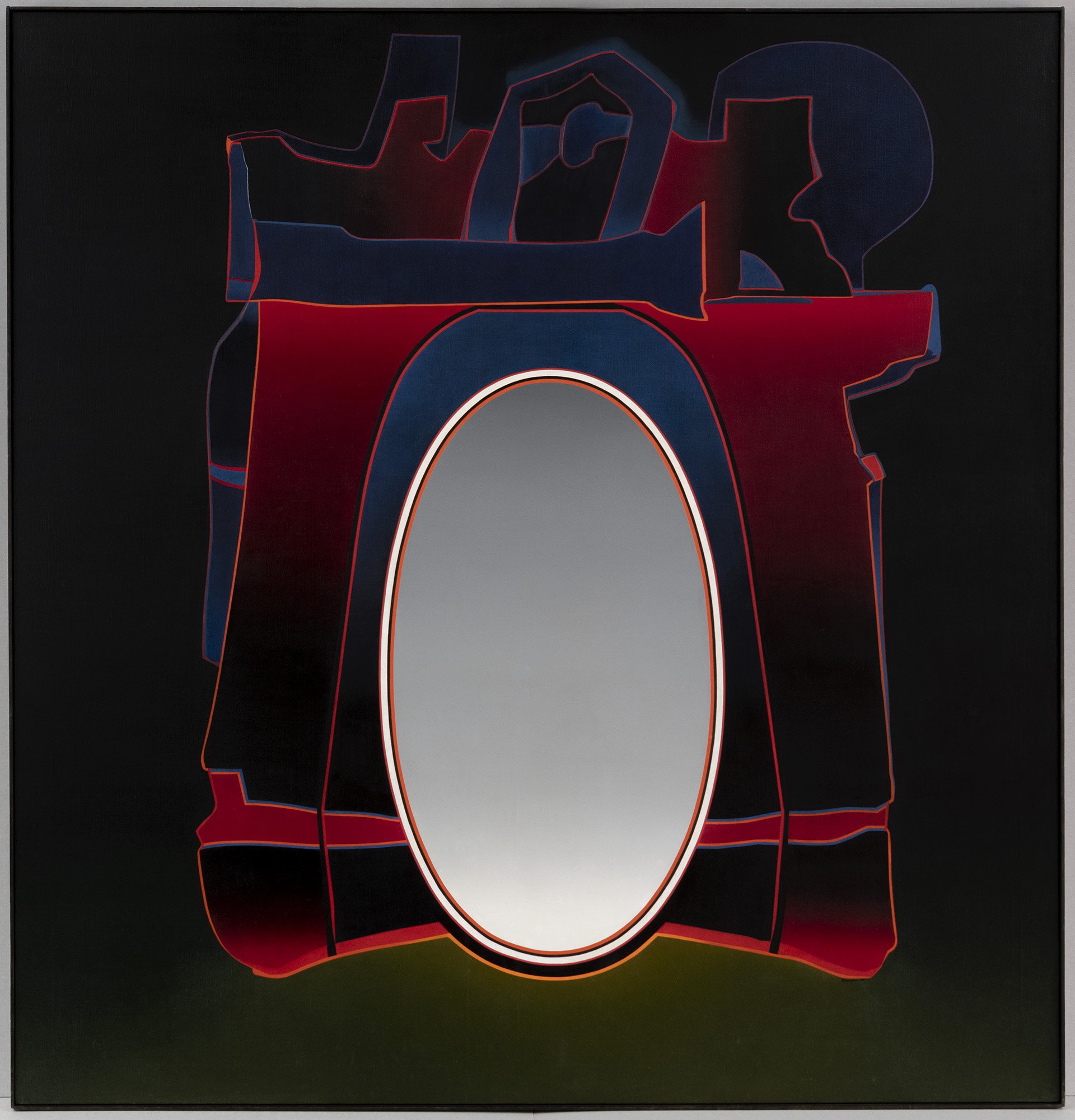

Deborah Remington, Aldwych, 1973, Oil on canvas, 236.2 x 315 cm. Image courtesy the Deborah Remington Charitable Trust for the Visual Arts and Bortolami, New York.

Margaret Mathews-Berenson, also known as “Peeky,” director of the Deborah Remington Charitable Trust, offered Painting Diary a series of incisive reflections on her longstanding friendship with painter Deborah Remington (b. 1930). Throughout our conversation, Mathews-Berenson shed light on Remington’s production techniques, radical worldview, and maverick sensibilities; she also traced the evolution of the artist’s distinctive bodies of work, which were in a perpetual state of reinvention until her passing in 2010.

Many of Remington’s paintings, such as Devon, 1969, and Aldwych, 1973, were shaped by diverse influences that ranged from explorations of light, shadow, and unorthodox color palettes, to her deep curiosity surrounding the disciplines of Chinese and Japanese calligraphy. Despite their visual reference to mirrors, they were in fact investigations into “otherworldliness,” evoking views through portholes into the intergalactic unknowns of Earth’s outer-spaces, captured by astronauts during the early days of the Space Age. Over the years, Remington’s style evolved dramatically, as seen in later, more abstract works like Santee, 1986, and Troas, 1987.

During our conversation, Mathews-Berenson recounted Remington’s early life, emphasizing her role as the only female founder of the 6 Gallery in San Francisco, where, in 1955, Allen Ginsberg famously recited Howl for the first time—a pivotal moment for the Beat Generation. She later shared how, when she first met Remington in 1986, their mutual love for the East Village art scene sparked their ongoing relationship. We also discussed Remington’s second solo exhibition at Bortolami gallery, Mirrors (6 September–26 October 2024), which coincided with the release of a long-overdue monograph, published by Rizzoli/Electa. The catalogue serves as a critical survey of the artist’s work, and details her pivotal role as a renegade figure in post-war American painting.

Today, as a key custodian of Deborah Remington’s legacy, Margaret Mathews-Berenson ensures the artist’s transformative contributions to American art receive the recognition they have always, rightfully, deserved.

Clare Gemima: Peeky, as someone completely immersed in the world of Deborah Remington, how have you managed her estate since her death in 2010, and have you gained insights into her life as an artist that you were completely unaware of before taking over what is now the Deborah Remington Charitable Trust?

Margaret Mathews-Berenson: Of course I have. We all have. There was much to learn. She kept a file of correspondence that was extraordinary. It even included her drawings when she was eight years old. I think even at that early age, she was very much aware that she was going to be an artist. That was how she was going to spend her life.

Her mother started taking her to art classes and hired a private tutor when she was quite young. Her mother found a class in nearby Philadelphia. Deborah grew up in Haddonfield, New Jersey, a suburb, basically, of Philadelphia. Her mother took her to the Philadelphia Art Alliance, where she drew from nude models along with the other students. She was the youngest one there, and that’s how it all began. She was keenly aware that her future was going to be dedicated to art. Deborah was always drawing as a child, and her mother saw that she was talented and wanted to offer her the opportunity to explore. I think her mother felt that this was the right thing for her to do.

CG: Did she have a close relationship with her mother and father?

MMB: Her relationship with her father was much closer, much deeper, but he died when she was fourteen, so she and her mother were left to fend for themselves. Her mother felt that she wanted to distance herself from the Remington family, with whom she didn’t completely get along, although she had nursed her husband through four years of illness. Her mother made the decision to leave the East Coast, and they moved to Pasadena in 1945.

That same year, Deborah was enrolled in a very progressive school out there. That’s where she began to meet some of the young people she would eventually go to school with at the California School of Fine Arts, later called the San Francisco Art Institute (SFAI). The classes at the school were extremely important and groundbreaking, filled with progressive teachers who had just returned from World War II, living life as if there was no tomorrow. On the battlefield, another day wasn’t guaranteed. I think this was one of the underlying attitudes of the Beat Generation, which Deborah embraced. It was a liberal world, and women had a voice.

CG: Did she study under Clyfford Still?

MMB: Well, everyone says that she studied with Clyfford Still because he taught there at that time. Every student knew him because he was an important figure, particularly to the abstract expressionist group that was emerging. Although Deborah did not take classes officially with him, it is certain that he would have known her work and was among the professors who were present during the many critiques that professors gave students on a regular basis. She did know him well and was aware of his reputation as a harsh critic, especially where women were concerned. He had a reputation for literally making women cry during their critiques. I’m sure she witnessed that or had heard about it, but never took a class with him. She did take classes with Wally Hedrick, David Park, and Hassel Smith, among others, and was no doubt influenced by Clyfford Still’s dynamic expressionist work.

Deborah Remington and four of the founders of the 6 Gallery, including Jack Spicer, Hayward King, Wally Hedrick, and John Allen Ryan (the sixth co-founder, David Simpson, is not pictured), San Francisco, 1955. Photograph courtesy of the Deborah Remington Charitable Trust for the Visual Arts.

CG: Can you speak to how her early days, including her time with the poet Jack Spicer and the founding of the 6 Gallery, influenced her later work? Is it true that this was the same gallery where Allen Ginsberg first read Howl in 1955?

MMB: There was a group of six painters and poets, including Jack Spicer. They joined together and founded the 6 Gallery, which was one of the first Beat galleries in the United States, and they managed it themselves. They curated exhibitions from the various members of the 6 and beyond, with other students from the California School of Fine Arts (SFAI).

And it was, yes. They invited Allen Ginsberg to read a poem called Howl—the first time he had read it in public. Deborah was the only woman founder—the only female! She was also responsible for naming the space. The artists got together and asked themselves “what should we call this gallery?” The conversation went on for hours, but they couldn’t find a name that they could all agree on. Finally, Deborah proposed that they just call it the 6 Gallery since there were 6 founders. Deborah was a take-charge, no-nonsense kind of person. When there was an issue that she was frustrated by, she would try to solve the problem and move on.

CG: She was self-directed her whole life, and seemed very autonomous. I guess experiencing loss at such an early age can make you that way…

MMB: She knew what she wanted for herself. Her mother collected Japanese prints and she was surrounded by art from the very beginning of her life. I think that was also a huge inspiration for her, and helped her look towards a career in art.

CG: Did Deborah ever travel to Japan?

MMB: She did in 1956, after she graduated from the San Francisco Art Institute—a decision unlike those of her peers. Deborah was familiar with Japanese culture through the prints her mother had collected, and through her two close friends at art school who were Japanese. These friends helped her find a family to live with and she left on a freighter—the only woman on board. She was in her twenties and braving a world that was totally unfamiliar. She remained in Japan until 1958, and spent most of her time living with a family in Tokyo.

At a certain point, she got fed up with being told what to do because Japanese mothers and fathers would direct their daughters very specifically as to how they should behave and dress. She learned not only how to speak Japanese fluently, but also what the culture expected of a young woman. She learned Japanese tea ceremonies, wore kimonos, and even helped her Japanese mother and sister make kimonos. She also studied Japanese and Chinese calligraphy very seriously, which I think helped her develop an aesthetic. The technique was controlled and quite the opposite of abstract expressionism, even though her gestures of calligraphic strokes can come across as very fluid and free.

This discipline taught her something that she would later introduce into her work when she returned to San Francisco. In addition to studying Chinese and Japanese calligraphy, she supported herself by working as a hostess in a Japanese restaurant and acting in some of the B movies that were being made there at the time, as well as a TV series called The Busy Housewife. She starred as the villain because she was tall and totally unlike the other actors, who were all Japanese.

In her mid to late twenties (1956 to 1958), Deborah was living in Japan, immersed in its culture. She is seen on the left posing in a traditional kimono amidst a blooming spring garden, and on the right in a tanzen jacket meant for colder weather. Credit: Courtesy of the Deborah Remington Charitable Trust for the Visual Arts. Special Collections and University Archives, Rutgers University Libraries.

CG: It’s fascinating that Deborah seemed to have traveled so much as a young woman.

MMB: She traveled widely and had friends in Morocco that she would visit periodically as well. They were good friends, and I know she enjoyed those visits. I think the bulk of her travels were inspired by the courage it took for her to go to Japan and insert herself into a culture that was so alien. While her peers and colleagues traveled to Europe, immersing themselves in European culture, she went to a completely unfamiliar place—and at a time when Japan was still recovering from World War II. Yet her Japanese host-family graciously received her and treated her like a daughter, which required strict rules of behavior. She also traveled from Japan to other areas of the Far East. She even took a job as a chef on a mountain-climbing expedition in Tibet.

CG: There’s a sense that she was selfless, self-aware, and also very curious.

MMB: Curious, for sure. She wanted to learn and expose herself to as much as possible. She didn’t want to limit her experience in Japan. And I think once she got back to San Francisco, she felt, “This is a small pond.” This is when she made her decision to move to New York.

CG: In Japan, did she decide to leave, or did the family encourage her to move on?

MMB: Well, she found the Japanese family to be very restrictive, so halfway through her residency she moved in with a couple of actors. That’s how she ended up on stage and TV. She later traveled throughout Southeast Asia. She was fearless, absolutely fearless. She would experiment with anything that she felt she wanted to learn more about. While she was there, she didn’t make any artwork of her own. She instead focused on the discipline required to learn calligraphy under the tutelage of experts.

She returned to San Francisco in 1958, where she had an apartment and began to establish herself in the art world. She carried a sketchbook and wandered around the Bay Area marshes, where she made sketches inspired by calligraphy techniques she had learned in Japan. Deborah translated the discipline of calligraphy into these wonderful, free-flowing, and expressive pen-and-ink drawings that related to the movement of the grasses along the bay, which she was observing from life.

CG: Did Deborah’s calligraphic understanding translate into her earlier paintings? The pieces referred to as “mirror” works?

MMB: When she returned to the Bay Area, she began experimenting with more disciplined compositions, creating shapes that floated in the way that calligraphic strokes float on paper. She was transferring this knowledge and understanding into large-scale painting. One of the first paintings she made in this series was Statement, 1963, which is now in the collection of the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. It was a transitional piece that led to the iconic, hard-edge mirror work that you’re referring to. But in Statement, you see a combination of gesture and discipline, harkening back to the very specific type of instruction she received in Japan.

She also dealt with a limited palette, based on shadow and light, and I think her experience with calligraphy led her to an overall understanding of what went into a gray scale. Gray-scale dominant compositions became a strong theme as she moved through the rest of her career, although she would punctuate her works with bright colors: deep cadmium reds, and deep Prussian blues. It was a very limited palette.

CG: At a recent ArtTable event hosted by Bortolami Gallery, you shared a poignant memory of speaking with Deborah during what seemed to be the final stage of her life, where she asked you to take on the responsibility of managing the Deborah Remington Charitable Trust. I’m curious about the status of her artistic archive at that time—did you have to build everything entirely from scratch?

MMB: Not entirely, no. Deborah was a scrupulous record keeper, and a pioneer in the use of databases during the early days of Mac computers. But before her digital database came into effect, she was keeping 4 by 6 cards with a slide insert that contained detailed information about every single one of her works: medium, date, exhibition history, provenance, etc. So, all of that was in place, but we had to create a complete inventory of what was left in the loft. Our responsibility was to take account of everything, make sure it was in the database properly, and add to it what wasn’t there. We definitely didn’t start with nothing.

But getting back to my moment with Deborah—yes, I was summoned to her bedside. She was in hospice care at Mary Manning Walsh Nursing Home on the Upper East Side. It was very sad to see her. She had lost a lot of her hair. She had been treated for lung cancer, and brain cancer, but she still had her usual strong and gravelly voice. She said to me, “I want you to take over when I’m gone.” Which, of course, made me cry. Even though I knew that was the reason why she called me, it still had a profound impact on my emotions. Yet I also had no real concept of what it would mean to take over an artist’s estate—I had no previous experience.

Deborah Remington, Mirrors, Installation view, Bortolami, New York, 2024. Images courtesy Bortolami, New York. Photos: Guang Xu.

I was an independent curator and art advisor for 25 years and later the Director of the Drawing Society. As an art advisor, I worked for a number of corporate art collections, including BMW and various ad agencies—bringing art into the workplace and making exhibitions within the company from which people could actually purchase works. They were encouraged to do so.

We hosted receptions and invited people to meet the artists whose work adorned their walls. It was an exciting time. I met Deborah during this period. She was lively, feisty, and she explained what she wanted out of life. Fast forward to seeing her confined to a bed in a nursing home, and knowing she only had a short time to live was truly such an emotional experience. Beyond that, my response to her was, “I have no experience doing this, but I’ll do my best.” She told me “Well, you have to do for me what Leah Levy did for Jay DeFeo,” and I said, “You mean with her Rose going to the Whitney?” She said, “Yeah, that and more.”

CG: No pressure…

MMB: I had no idea who Leah Levy was, but one of the first things I did after Deborah’s memorial service was contact her. We talked, became dear friends, and have continued to stay in touch. Jay DeFeo’s and Deborah's works have been shown together in several exhibitions since her passing. I was charged with the task of bringing her back to life, so to speak.

CG: Was there anyone that was closely working with Deborah at the time? Did she have assistants in the studio?

MMB: She continued to have studio assistants into the 90s. A lot of them were students from Cooper Union. But she was mostly working alone at the time I began to get acquainted with her.

A very close friend and former studio assistant of Deborah’s, Cheri Smith, became one of the members of the Remington Trust. It’s a very small organization. There are only four of us: Cheri Smith, attorney Phyllis Landau, myself, and the most important member, Craig Remington, a cousin of Deborah’s and the executor of the estate as well as the Trustee. We met as a group, and Cheri and I had private conversations about how to go about doing the things we needed to do. Being a photographer, she said, “I’ll come to New York, bring my camera, and we’ll set it all up.”

We organized ourselves at the loft with an appraiser and art handlers. We went through all of the inventory, and photographed and recorded it in the database. That was the very beginning. We also had to sell the loft and her country home in Pennsylvania. Working in her loft gave us the opportunity to look through all of Deborah’s belongings, everything from her recipe books to her clothing, in addition to all of her important artworks, plus her library of art books and catalogues. Then we decided what to do with it all.

Zanthus, 1983. Oil on canvas. 74 × 67 in. Image courtesy the Deborah Remington Charitable Trust for the Visual Arts and Bortolami, New York.

We also had to decide where to donate her archives and correspondence, which was unbelievably prodigious. She corresponded with so many people over the years. She kept copies when she was typing, but a lot of them were handwritten. I think that many of them may have been returned by her request so she could keep the originals for her own archive. We also had to ensure the archive would be accessible to the public. Archives of American Art obviously occurred to me, but I reached out to them and never heard back.

A couple of friends of mine were working at Rutgers at the time, and suggested that because there was a very strong presence of women in their archives, I should consider donating it to them. They were the perfect choice because Rutgers was in New Jersey, and Deborah’s hometown of Haddonfield was also there. It just felt like it was meant to be. We hired someone at Rutgers to really look at the archive in depth and provide us with a detailed inventory. It’s now all organized by folder and item number, and accessible to students, faculty, and the general public.

Rutgers has worked very conscientiously with us, so we’ve given them grants to use for other projects in their archives, particularly Miriam Shapiro’s and various others.

CG: When the Trust gives a grant to an institution like Rutgers, what is the grant used for?

MMB: They make proposals to us. In the case of Rutgers, we provided a grant to hire someone to catalogue the Remington Archives. We’ve also given grants over the last five or six years to Rutgers for ongoing projects. We’ve also contributed to other institutions that Deborah was connected to, including the National Academy of Design. We’ve given grants to the Artist Endowed Foundation Institute, which is part of the Aspen Institute, for ongoing research and DEAI projects, and also to Cooper Union for digitizing various objects of ephemera that were made during the time that Deborah taught there, from 1969 to 1997.

Every grant we’ve given has a purpose, and we review these on a yearly basis, usually giving two to three per year. They’re very small grants, but we believe the money goes to good causes. We gave a couple of grants to the Tamarind Institute at the University of Albuquerque in New Mexico because Deborah studied printmaking there and made wonderful prints with one of their master printers. We have also given a number of grants to the San Francisco Art Institute Legacy Foundation + Archives.

CG: So the proposals differ every time?

MMB: Yes, exactly. We don’t advertise, so there’s no competition. We only invite, and usually discuss what the grant will be prior to asking for a proposal.

It is always so rewarding to share Deborah’s paintings and find new ways to present her work. Deborah was pretty much forgotten by her death in 2010. It is sad when an artist’s star fades; it is redeeming when their work re-emerges and continues to impact and influence culture. I think what she created in her life was greater than herself, which is really every artist’s dream. Her work is so singular, so puzzling, and so unlike what was being made by her peers in her own time. She is a true Mannerist of postwar American painting. Probably the best decision Deborah ever made was to entrust her Estate to Margaret Berenson, whose dedication and enthusiasm has made her reevaluation possible.

– Evan Reiser of Bortolami Gallery, 2024

CG: Let’s discuss Deborah’s paintings from Bortolami’s recent exhibition Mirrors. They look as though they could have been painted yesterday. I’m curious—what condition were the works in when you originally found them, and how do you actively ensure their preservation?

MMB: Deborah was her own best preservationist. She had studied all sorts of master techniques of painting, and used a typical Maroger medium which Vermeer and other Renaissance painters used. She was meticulous about her surfaces, particularly in the works from the 70s, because each painting is actually painted twice.

Devon, 1969, is an early example of a mirror image. Deborah would sketch out the composition on a gessoed canvas and then once she completed the composition with precisely chosen colors, her assistants would help her paint in the lines, which were very important. These lines accentuate and delineate various aspects of the composition. She would then allow each paint layer to dry thoroughly before finally repainting the same composition on top again in the exact same colors. As you can see, her palette ranged widely in some of those early pieces, like Aldwych. Deep gray-blacks with slight reddish, maroon accents. There’s a luminosity that can only exist through that “dual layer” approach to painting. In terms of conservation, we’ve had very few issues, but they’ve all been resolved successfully because we found a wonderful conservator who treats Deborah’s work, and readily understands what needs to be done.

Devon, 1969. Oil on canvas. 73 × 71 in. Image courtesy the Deborah Remington Charitable Trust for the Visual Arts and Bortolami, New York.

CG: Although Deborah had help in creating those perfectly sharp and graphic accentuating lines, they almost look too exact, as if they were digitally rendered. How were they constructed exactly?

MMB: You know, most artists would take a long piece of tape and run it close to the edge, but Deborah didn’t do that. She took tape and cut it into 1.5- or 3-inch-wide pieces, and would adhere them one-by-one sideways along the edge of her canvas when creating the outlines of her compositions. There might have been hundreds of pieces of tape in order for her to achieve absolutely clean lines.

She had numerous studio assistants helping her—most were women. Many of them talked about how generous she was with sharing not only her techniques and approaches to painting, but also in advising them about their personal lives as painters. She would tell these women to be cautious about getting married and starting a family, because it could interfere with their careers. Some of them objected to that, but many understood what she meant, which was that one had to choose between focusing on a career or a family—the two did not mix, at least during the time in which she emerged as an abstract expressionist in the 50s and 60s. Interestingly, she married a man once, an actor and theater producer. They were married for about 18 months, and then she said, “That’s enough for me,” and returned for her Bachelor’s degree at SFAI.

CG: I am getting a sense that paintings like Aldwych and Devon weren’t always necessarily referred to as mirror works?

MMB: The works can be seen as relating to mirrors, but I think the unearthly glow we see might also have been influenced by her interest in the space age, which was gaining ground in the 70s. They can also serve as a reference to a kind of indeterminate space that astronauts were seeing through portholes into the unknown. Personally, I don’t always think about the works in relation to mirrors. I think about them as views into other worlds. She was an avid reader of Scientific American Magazine, and followed the developments of the space age with great interest. The luminous glow and sense of infinity, I think, comes from what she was seeing in those images that were being sent back to Earth from the moon and space.

Aldwych, 1973, Oil on canvas, 236.2 x 315 cm. Image courtesy the Deborah Remington Charitable Trust for the Visual Arts and Bortolami, New York.

CG: Did Deborah ever refer to these paintings as personally reflective or introspective? Did she ever make commentary about her own work?

MMB: Aha, well… She was a total woman of mystery. She would say things like, “I see myself as a giant IBM machine of sorts… stuff gets fed in and then it comes out. How it comes out is what you see.” Everything she saw and experienced seeped into her head, her body, and was expressed in the work she made.

In 1983, she received her first diagnosis of cancer, which was breast cancer. At the same time she was undergoing treatment, she was also putting together her first solo show for Paul Schimmel at the Newport Harbor Art Museum (now the Orange County Museum of Art). Working on the show with that hanging over her really pushed her to think about how she might change direction.

Regarding introspection, the gesture from her Ab-Ex days re-emerged in 1983 and continued from 1986 to 1989 with works like Santee and Troas. In a certain way, I see them as still lives. Perhaps she’s looking at her easel, her desktop—but, really, she’s looking inward. Though she would never ever talk about what the work represented. Having a studio visit with Deborah was very difficult because she would just wait for you to talk, and sometimes there were these very awkward silences—what was anticipated, what did she expect me to say? She always pursued her own vision and her own vision changed, and occasionally it changed drastically, as seen in these late 80s gestural works.

[L–R] Santee, 1986. Oil on canvas. 53 × 52 in. Troas, 1987. Oil on canvas. 56 × 52 in. Image courtesy the Deborah Remington Charitable Trust for the Visual Arts and Bortolami, New York.

CG: Do you recall any objective reactions or criticism she received regarding her shift in style, or any that marked a pivotal moment in her career?

MMB: Well, that’s an interesting question. We met at Jack Shainman’s in the East Village in 1986 when I stopped in to see an opening there. I loved the East Village scene and followed it enthusiastically. I had never met Deborah before, but when I walked into the gallery, she was standing in the back with her arms folded, as if in judgment, and then she stopped me, introduced herself, and asked, “Well, what do you think of the gallery?” and I said, “I love Jack’s gallery. I love him. I think he’s a wonderful dealer. He’s very interesting, and everything he shows is as well.” She replied, “Okay then, let’s go get some weasel piss.”

She was referring to the terrible white wine being served at the opening. Anyway, we got wine together, ended up having a long conversation, and then she invited me to her studio.

Perhaps she was reassured by what I said about Jack, as she invited him for a studio visit and had a solo show with him in 1987, just a year later. It was very well received, and even reviewed in the New York Times. It included some of the works we just talked about, like Santee and Troas. These works showcased a radical departure for Deborah. People who knew her previous work from the 70s didn’t always necessarily understand it, but the reviewers were enthusiastic. Her style changed after this, and then evolved yet again.

Penrith, 1989. Oil on canvas. 74 × 50 in. Image courtesy the Deborah Remington Charitable Trust for the Visual Arts and Bortolami, New York.

She applied for a Guggenheim grant in 1984 because she knew she wanted to continue with this sort of gestural work. It was the second or third time she’d applied, and finally she received it. Her application talked about how necessary it was for her to return to the gesture of her Ab-Ex days, and that was her intention—to loosen things up. I think this also had to do with her diagnosis. It was such a major event in her life that came with many adjustments and forced her to learn to welcome change.

She was moving on with energy and confidence in her work and in 1985 she bought a house in the country. It was always her dream to have a country home, and from that time through to the early 90s, her work began to reflect the time she spent there. As she started to cultivate her own garden—growing and preserving her own vegetables—her paintings became a lot more organic. That was very important to her too, getting back to the earth, the soil, growing flowers, and shooting any groundhogs that dared venture onto her property.

Consider a work like Penrith, which almost looks as if it has seeds floating in it. Those seeds later would turn into shards, particularly in later works like Encounters, where things look as if they’ve exploded. She granted herself permission to let things explode, and it’s important to remember, her battle with cancer continued.

She was diagnosed with lung cancer in 2004, and struggled with the emotional complexity that came with it. However, the dual-like forms in Encounters—sometimes recognized as lungs—actually refer to sketches she made of the famous Egyptian Narmer Palette on a visit to Egypt in 1980. They reference a kind of identity, and obviously the idea of rebirth, or life after death. I don’t see Encounters [the last painting she made], as a negative representation of her demise. Yes, she’s dealing with her illness, but to me it feels more like there’s a fight going on. Deborah never gave up. Never gave up on anything she ever did.

You might sense that the painting is an amalgam of her ideas about life after death. But also, she had a lifelong interest in heraldry. To her, heraldry was a reference to family, heredity, and the afterlife. Although these forms could reference lungs, I think they also reference continuity and the ongoing spirit of life after death. The sharp angular shards also relate to vulnerability, and although they are shards, they are not breaking the form. The form remains complete.

Encounters, 2007. Oil on canvas, 72 × 67 in. Image courtesy the Deborah Remington Charitable Trust for the Visual Arts and Bortolami, New York.

I think everybody has a different kind of reaction to Encounters, and they are all legitimate. I don’t want to present any arguments. I expressed what I feel, and whatever you feel has equal legitimacy. I think everyone is entitled to interpret, and this is why Deborah’s work is so compelling, because it allows room for all kinds of interpretation and contemplation.

CG: Peeky. It’s been a privilege to discuss Deborah Remington’s life and work with you, and I’m grateful for the stories and perspectives you’ve shared. Thank you again for your time and dedication to our conversation.

MMB: Thank you, Clare.

—

Mirrors is the second solo show for Deborah Reminton at Bortolami. It coincides with the release of a major monograph on the artist, published by Rizzoli/Electa in 2024. The book represents a long overdue survey of the work of yet another under-recognized woman artist: a renegade in every sense of the word, who well deserves critical attention.

Margaret Mathews-Berenson has served as the Director of the Deborah Remington Charitable Trust since 2010. She has had a long career as an independent curator, art educator, and advisor with special expertise in contemporary art and photography. She founded her own business in 1984 following a career in museum work (at the Philadelphia Art Museum and Metropolitan Museum of Art) and book publishing. Since then, she has advised collectors (corporate and private) and curated numerous exhibitions for museums, galleries, and non-profit institutions throughout the United States. Among her recent exhibition projects are Homeland [IN]Security: Vanishing Dreams at the Dorsky Curatorial Programs space in Long Island City, New York and Women and Prints: A Contemporary View at the Ruth Chandler Williamson Gallery, Scripps College in Claremont, California. A dedicated arts professional and advocate for the art community, Berenson served on the boards of ArtTable, Artists Space, the Dieu Donné Papermill, and Swiss Institute, among others. From 1997 to 1998, she was director of The Drawing Society and editor-in-chief of Drawing magazine. An accomplished lecturer and writer in the field of contemporary art, her articles and catalogue essays have been published in ARTS, American Artist, Drawing, The Pastel Journal, and Sculpture magazines. Through her tour program, Art Today, she offered specialized lectures and travel opportunities, with recent tours including The Snow Show in Finland, as well as biennials in Miami and New Orleans. As an arts educator, she taught in the graduate program of Arts Administration at New York University, the International Center of Photography, and the Christie’s Masters in Education Program. She also served on the faculty of the 92nd Street Y in New York.

Clare Gemima regularly contributes to publications such as: Painting Diary, Eazel, Impulse Magazine, Artefuse, Contemporary HUM, Art New Zealand, Brooklyn Rail, Two Coats of Paint, Whitehot Magazine, EV Grieve, AWT, Wide Walls, Frieze, Passing Notes, New Women New York, and Artsy. Her work focuses on building scholarship for immigrant artists pursuing their artist visas, as well as emergent, established, and historically overlooked practitioners based in New York and abroad. Her work has allowed her to travel across the United States and internationally, where she has reviewed exhibitions and interviewed artists showcasing at esteemed galleries, archives, museums, and fairs, including Untitled Art Fair (Miami), the Museum of Contemporary Art (Chicago), The Andy Warhol Museum (Pittsburgh), New Museum (New York), Honolulu Museum of Art (Hawaii), and the Venice Biennale (Italy).