Becoming our ‘visual skin’

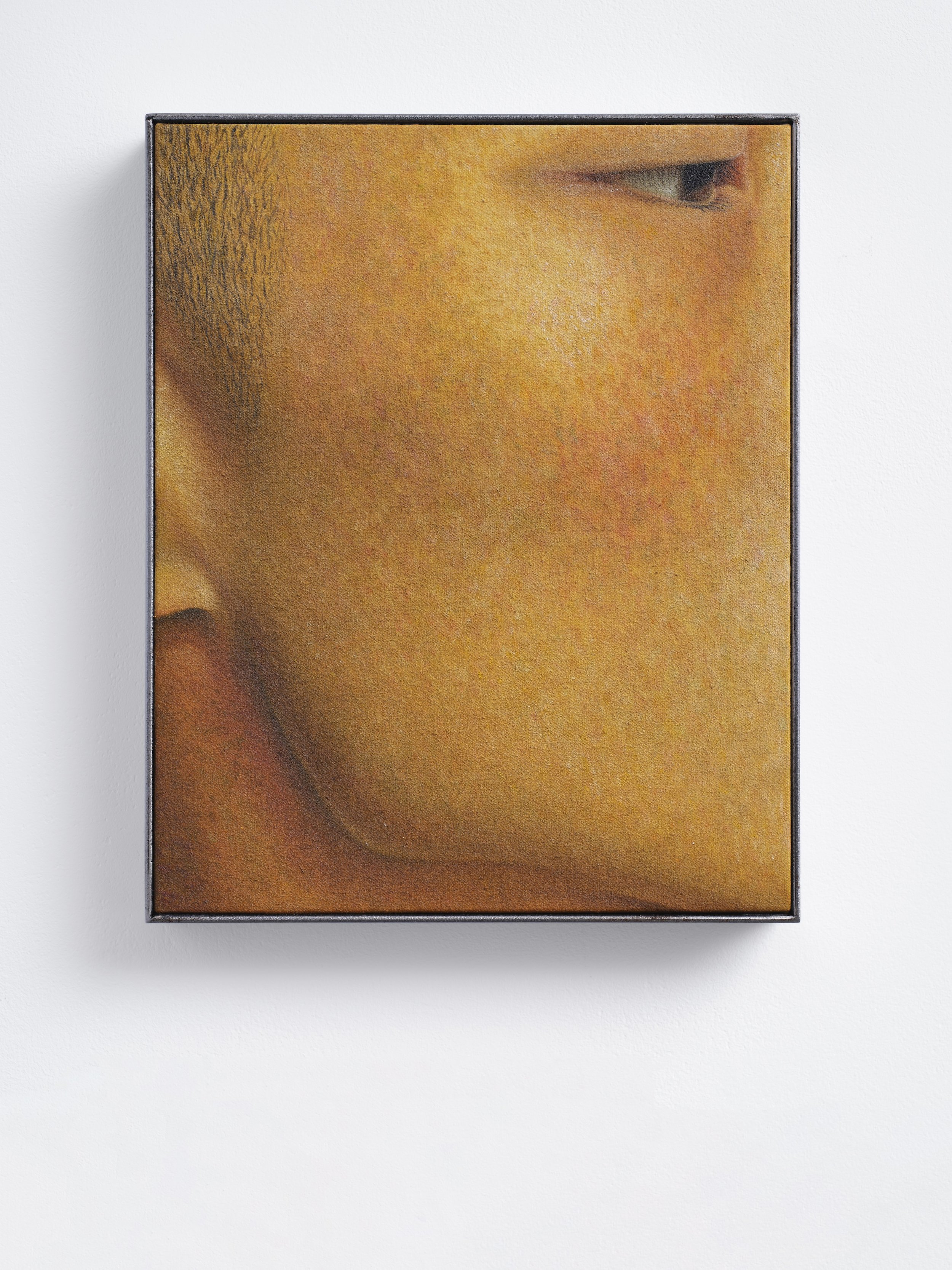

Sang Woo Kim, You’re looking at me 008, 2024, Oil and acrylic on canvas, 36 x 25.8 x 3 cm. Courtesy the artist and Herald St, London. Photo by Jackson White.

If I may, I will start with something to ponder: do you know what you look like? Do you have a good idea about how others visually perceive you? We are living in a world that is overrun with images, not only through marketing that is ever inching its way towards our intimate lives and spaces, but those depicting ourselves. My years in a convent girls’ school reinforced the idea that having unlimited access to our reflections was a superfluous waste of time and energy. Punishment ensued for any deviations from the school uniform, and an aesthetic austerity was enforced when it was decided that mirrors in the communal bathrooms would be removed. There was something rather hysterical about this executive decision, which followed the recruitment of a new headmistress. Sinisterly bare non-spaces emerged, where automatically one’s head would look up to innocently check one’s reflection. Instead, only a blank white square with wall fixture markings remained. While this removal seemed profoundly militant and harsh at the time, there was a clandestine, and perhaps retroactive, kindness in removing the need for young women to have access to their reflections at times of learning and socialising with friends. Without these mirrors, at the age of fifteen, I could say that I didn’t know what I looked like at every conceivable moment. This was also before the days of social media, or at least the incessant, ubiquitous, bottomless-pit of algorithm-fiending social media, and phones were strictly contraband on school grounds.

But what if I did have access to a phone with a front-facing camera (albeit unlikely in 2009), through which I could check my clumpy mascara and Dream Matte Mousse foundation every few minutes, to make sure I was presentable to an unknowable audience, one that extended beyond people I know in real life? How about an endless array of filters for my friends and me to use on social media? There was no possibility for me to manipulate and shave down my nose to look like a Kardashian, or the cast of Selling Sunset, and therefore reproduce myself with an Instagram Face. What would have been the psychological price to pay after smoothing out my complexion to look like a balloon, brighten my eyes like an anime character? The list goes on. Of course, this isn’t a science-fiction kind of ‘what if?’, it is the reality of teenage girls, young women, and essentially every other demographic regularly using social media.

When we view our face through technological means, we realise that we never look the same. There is always something missing, and the transient nature of our appearance is exposed. Technology’s increasing affordability, and the need to Be Online in the post-digital age, has democratised the sharing of one’s image. In matters of the ‘self’ and the portrait, then, what is the function of the contemporary portrait, and what defines it? Historically, portraits produced to assert power and status were reserved for the upper classes, but now we play the roles of subject matter and creative director in tandem. Artist and muse.

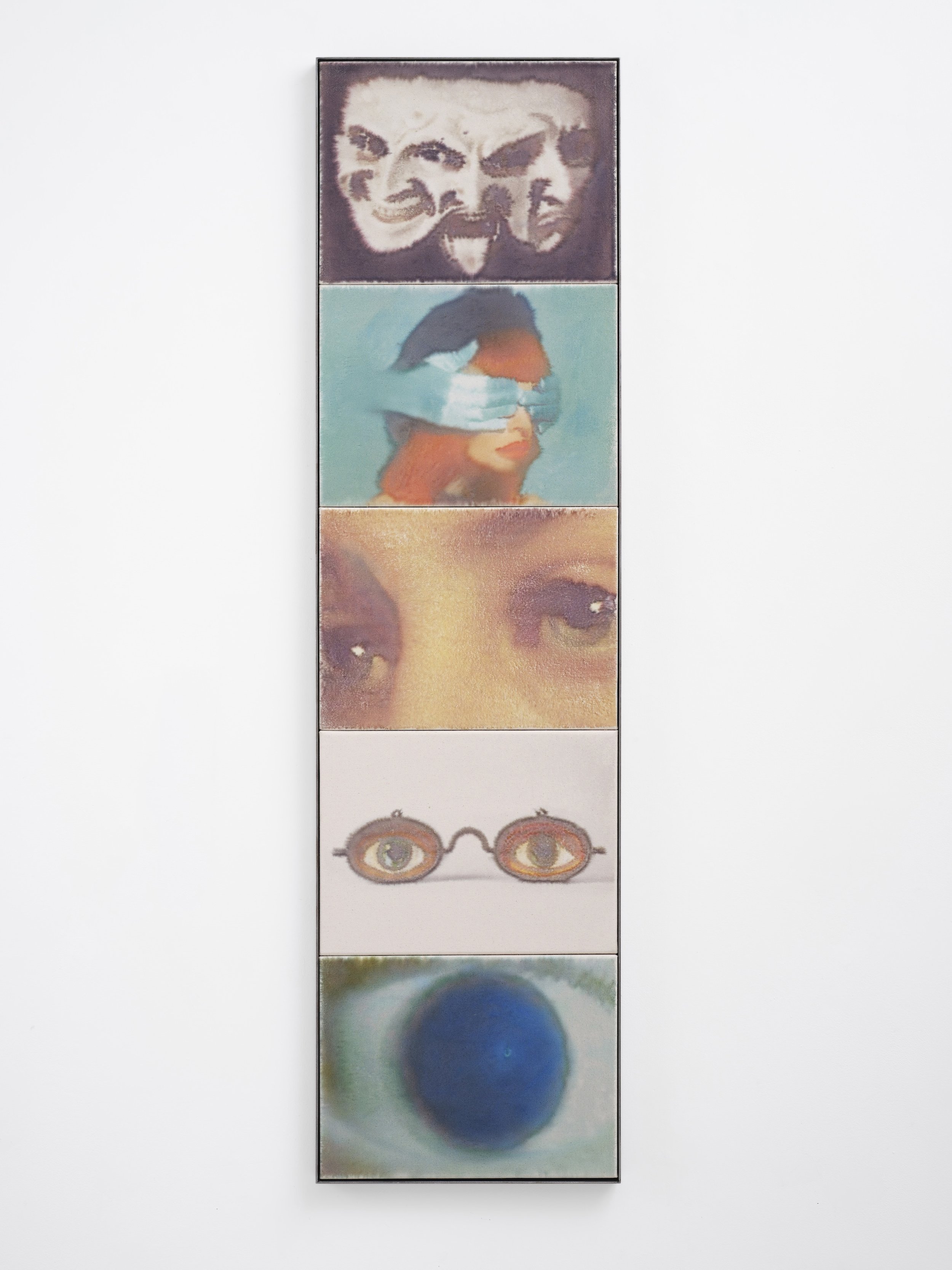

Sang Woo Kim, Ways of Seeing 010, 2024, Pigment dye transfer on canvas, 155.2 x 42 x 3 cm. Courtesy the artist and Herald St, London. Photo by Jackson White.

The contemporary, psychologically informed complexities that we feel towards both our own and others’ bodies have undoubtedly shaped contemporary painting and portraiture. More than ever, we see bodies in situ; the contrived nature of the traditional portrait is rendered meaningless and anachronistic in the twenty-first century, reserved for the royalty and upper echelons it was intended for. Even the official 2022 portrait of the Prince and Princess of Wales by artist Jamie Coreth sees them looking away, almost like a candid shot, which is rather amusing given the painstaking nature of realism portraiture, and the affirmed permanence of the institution of royalty.

Yet, the precision, intensity, and commitment of traditional portraiture does not fully compute in the twenty-first century. Existing in a world in which the online realm has successfully permeated every material and immaterial aspect of contemporary living, we can classify these conditions within a ‘post-Internet’ epoch. Artist Parker Ito describes this as an ongoing methodology, an unmoving way of life: ‘Now you can look at cave paintings magnified by a thousand times their original size online. That is more about a historical condition which we are living through and looking at art through.’ It is as if the temporal grounding of an individual artwork has become insignificant; we are accessing them and viewing them the same way, whether the artwork is in the room with us, or on a different continent, or in the case of digital art, physically located nowhere. I can visit my local art gallery and take photos on my phone to look at later, or I can look at installation shots from a gallery in New Delhi, and view them almost identically. We are everything, everywhere, all at once, and the full, static image no longer fits the post-Internet lifestyle, nor does it align with the way we view objects. In analysing the works of Sang Woo Kim, Celia Hempton, and Moka Lee, three contemporary painters working with different forms of portraiture, we find that two significant features of the contemporary portrait are fragmentation and dynamic action.

A visual fragmentation of the face is a bold means of defying the perceived concretisation and fixed state of the self that comes with one image, whether presented through the medium of photography or painting. London-based artist Sang Woo Kim confronts both himself and his own image reflecting back through society’s gaze; he presents himself through painting in a way that feels personal to the point of intrusion, and has stated that his treatment as a man with Korean heritage living in London has profoundly shaped the way he works. His paintings insert Kim into the history of portraiture, taking inspiration from portraits throughout history while directly addressing the barriers presented by racism, xenophobia, and varying forms of ‘Othering’.

Sang Woo Kim, The Corner 012, 2024, Oil on canvas, 28.5 x 23 x 3 cm. Courtesy the artist and Herald St, London. Photo by Jackson White.

As one example, The Corner 012 is a delicate painting that isolates the subject’s jawline and side profile, providing the minimum required to identify the sitter. Kim often uses himself as subject, and here is no different, but the intimacy between viewer and the artist (playing the roles of both artist and subject) is fascinating; the old adage ‘the eyes are the windows to the soul’ is discarded in the painting, with the artist taking back full ownership of the gaze. We will see exactly what the artist wants us to see, and nothing more. Our gaze will not be met. In the traditional setup of the portrait, the viewer is witness to a curated vision, depicted exactly as the sitter would like to be seen, flaunting material status as outwardly as possible; yet, in The Corner 012, Kim does not address the viewer, not even offering a cursory glance. We are nothing.

For his exhibition at Swiss gallery Sébastien Bertrand, Kim writes, ‘ultimately, it boils down to being present. I rarely concern myself with others’ perception of me, nor do I fully trust my own self-perception… after years of grappling with embarrassment over my image I had no control over growing up… and being haunted by countless misrepresentative images of me, I realised the necessity of reclaiming agency over my own image, my identity, and myself’. Of course, this is no small ambition, and it is the artist’s prerogative to gauge whether he has achieved this, and jostle with its potentials and possibilities, but in a world (and algorithm) that wants us to indulge our diaristic impulses and divulge our innermost selves, gatekeeping the self is an incredible piece of identity world-building. The medium of painting only serves this further; imagine a world where we shun the mirror and the camera, only to see ourselves in painting. Imbued with imagination, illusion, and perhaps a touch of delusion, we could paint ourselves anew.

By reflecting on my original question, ‘do you know what you look like?’, we are brought back to reality with a thud. Kim’s work reminds us that under the ‘Othering’ gaze, one cannot help but be hyper-aware of what one looks like, whether that is a particular feature on our face, a disability, our race, our gender, our defiance of gender expectations, our hair, I could go on. While there is a hierarchy of discrimination at play, everyone will understand this to some degree, and when something interests others, it becomes the part of ourselves we fixate upon. It takes a huge amount of un-learning and unravelling the patriarchal, racist, fatphobic, misogynist, and other discriminatory practices in which we are incubated and immersed our entire lives. For Kim, this is indeed a point of fixation, but one from which he emerges victorious. He is, surely, visible not only in his own terms and visual language, but in a way that is both fragmented and dynamic. There is movement in the way he depicts himself, only confirmed by the lack of gaze offered back to the viewer. He consents to being represented through his paintings, but retains a degree of anonymity; we are unlikely to recognise him in the street after bearing witness to works such as The Corner 012.

Part of the difference between contemporary portraiture and more general images of bodies is a question of consent, and what we may consider an expanded sense of consent. Not only was consent granted for the opulent portraits of centuries gone by, they were heavily ‘filtered’ and exaggerated, something that has been translated into our own times through technological means. With this asserted consent for images fixated and directed by the ego, how might other ways of fragmenting the portrayed self subvert this?

Celia Hempton, Surrey, United Kingdom, 20th September 2013, 2013, Oil on canvas, 25 x 30 cm. Image courtesy the artist and Phillida Reid, London.

Another London-based artist, Celia Hempton, gained renown for her series Chat Random (2014–), where her respective subject matter was sourced from the website of the same name, connecting strangers around the world via webcam. Dwelling in a setup bursting with both creative and perilous potential, Hempton then made portraits of the body parts she was exposed to, somehow both willingly and unwillingly. Users of these websites know what they are likely to encounter upon entering, but consenting to viewing is shaky territory. It is important to note that Hempton obtained the consent of the men she painted, but the performative aspect of posing on an anonymous webcam for the main purpose of titillation and pleasure is undeniably different to that of having one’s portrait taken.

Many works in the Chat Random series have a strong sense of the anonymous, with very isolated information available to the viewer, whether this is a first name, a geographic locator, or the date during which the encounter with the artist took place. Surrey, United Kingdom, 20th September 2013, for example, almost needs the viewer’s active participation in squinting to discern exactly what they are seeing. With their own genitals in their hands, our Surrey-based friend retains the anonymity and, most likely, the thrill of what they had initially accessed the website to do, with the addition of being a subject matter for a painting which will enjoy a longevity that many online interactions do not. Here we encounter the opposite of the mirrorless convent school; a triple bind in which Mr Surrey can view himself in the flesh, through the camera lens, and also through Hempton’s painting, with multiple perspectives all producing different effects and affects.

Celia Hempton, Sunshan, China, 26th November 2013, 2013, Oil on canvas, 31.5 x 35.5 cm. Image courtesy the artist and Phillida Reid, London.

Many people who posed for Hempton will not have been aware of what they look like from these particular angles, with no control over the artist’s finished painting. Hempton’s brushstrokes evoke the urgency, spontaneity, and clandestine nature of the interaction, and yet the sense of solitude permeates each work in the series. Whether Surrey, United Kingdom, 20th September 2013, or the more straight-faced, portraiture stylings of Sunshan, China, 26th November 2013, conveyed fully clothed and facing the camera bluntly, cigarette hanging loose, the sensation of loneliness behind the camera is palpable.

Something that cannot be overlooked is the power that lies behind the very creation of portraiture; whether it is the bourgeois individualism of sixteenth-century Europe, the audacious nature of Kim Kardashian’s coffee table book, Selfish, featuring nothing but photographs of herself, Sang Woo Kim taking back the power of the White gaze, or Hempton flipping the pornographic fetish gaze back onto men, there is power in revealing new ways of seeing.

Hempton’s works illuminate the Sexual Offences Act 2003, which states that one commits an offence if one sends a photograph or film of their genitals to another person, with the intention that they ‘will see the genitals and be caused alarm, distress, or humiliation’. In creating almost dreamlike aesthetics through her distinctive style of painting, the artist shows the subjects a new perspective on themselves; some are not particularly explicit, and those that are appear so fragmented from their human wholeness that their status as artwork seems to transcend their unique identity, and the activity taking place. This entire process is heavily laden with gendered customs and power dynamics; the criminality of what is called ‘cyberflashing’ (sending unwarranted intimate photos to strangers online) is mostly perpetrated by men, yet, Hempton subverts the dynamics of perpetrator and ‘victim’. This results in a fleeting intimacy that is sometimes lost with the traditional depictions of sexuality and masculinity, but which is more akin to portraiture.

Moka Lee, Hate Stranger 05, 2024, Oil on cotton, 91 x 91 x 3 cm. Courtesy the artist, Jason Haam Gallery, Seoul; and Carlos/Ishikawa, London.

Fleeting intimacy is something that Seoul-based Moka Lee also conveys incredibly well in her work. A recent body of paintings shows sitters not only undertaking mundane activities such as drinking a soda, they are often found either posing as one would amongst friends taking a photograph, or, as is the case in Hate Stranger 05, caught unaware. Her works depict mobile phone-camera quality so well that it is something of a dizzying experience at first glance to try and comprehend whether the works are paintings or prints. Lee calls herself a portrait artist, but purists may beg to differ. In reproducing far more casual scenes in her subjects’ lives, her work feels more fitting to our times than traditional portraits.

Whereas the purpose of a traditional portrait is to be the beginning and end of the viewer’s experience of the subject matter, contemporary artists like Lee are holding the door open through fragmentation and dynamic movement. We can never know the full story. In an interview with Artsy, Lee partially reflects Parker Ito’s comment quoted above, saying, ‘Instagram is a medium where you can observe people up close. The intentional elements in the photos people post are intriguing’. These ‘intentional elements’ are something of a visual code in the artist’s work, and while one may be able to ‘observe people up close’ in a parasocial and literal sense, by zooming into personal photos, an emotional gap emerges as to the authenticity of the images being replicated. There are many ongoing critiques of social media, but Lee’s work harks back to the fun of posting, evoking the energies of being young and spontaneous, while working in the medium of painting, which is saturated in longevity and craft. The sense of fun and youth in Lee’s work functions despite the ways in which social media culture steals the essence of youth from its users through merciless consumerism, comparison, and constant challenges to meet (or beat) the algorithm.

Moka Lee, Clapping Hands, 2024, Oil on cotton, 45.7 x 45.7 x 3 cm. Courtesy the artist, Jason Haam Gallery, Seoul; and Carlos/Ishikawa, London.

And yet, the experience of what youth is, and how it feels, continues to change. My years in a convent school, with its austere rules and often atavistic customs, felt like a constant flow of punishments, dished out to the whole school population regardless of individual behaviours. A lack of mirrors felt cruel, withholding; but what an obscure pleasure such an action would be now. Nothing to check while we were working, studying, and living our lives outside of being concerned about the minutiae of our physical appearance. In essence, the punishment worked; short of catching our own reflections in windows and glass doors, we had no choice but to get on with our day without the distraction of what we looked like. A spilt drink on a shirt or a smeared mascara stain would go unnoticed until too late, or by which point the care had simply moved on. We dream of such a freedom now; as soon as we become visible in the public domain, the onslaught begins, whether that is external or internal.

As soon as we stake our right to take up space, the world takes that tenacity and places us within a context, a framework (whether that is based on our race, ethnicity, sexuality, gender expression, disability, or something else), and starts writing our future story, imbued with stereotypes, clichés, and limitations. Through exploring and experimenting with portraiture, contemporary artists such as Kim, Hempton, and Lee look at the power dynamics prevalent in traditional portraiture and subvert them, with Kim’s journey of self-discovery through fragmentation beyond the aesthetics of his own face, Hempton’s disruption of realism through an abstracted, depersonalised fragmentation, and Lee’s directed, fragmented snapshots of youth documented through painting, we are reminded of our compartmentalised perspectives and selves. Kim’s creative decision to focus only on the eyes or the side of his face, and to exhibit these works alongside cultural references held dear to him as an individual, ‘builds up and breaks down boundaries to create a visual “skin” composed of nostalgia and recollections’. Thus, for Kim, Hempton, and Lee, and all of us as online denizens, the ‘visual skin’ transcends the body. A great deal of potential could come from us all creating our own ‘visual skin’, without hurtling unrelentingly towards the Black Mirror zone. Some might perceive our social media profiles as playing this role, but as individuals and a society we must strive for something more meaningful than begging for scraps from Zuckerberg. So, the question ‘do you know what you look like?’ is not the same question I initially posed. Instead, we can ask, ‘what parts of yourself do you see that others do not?’